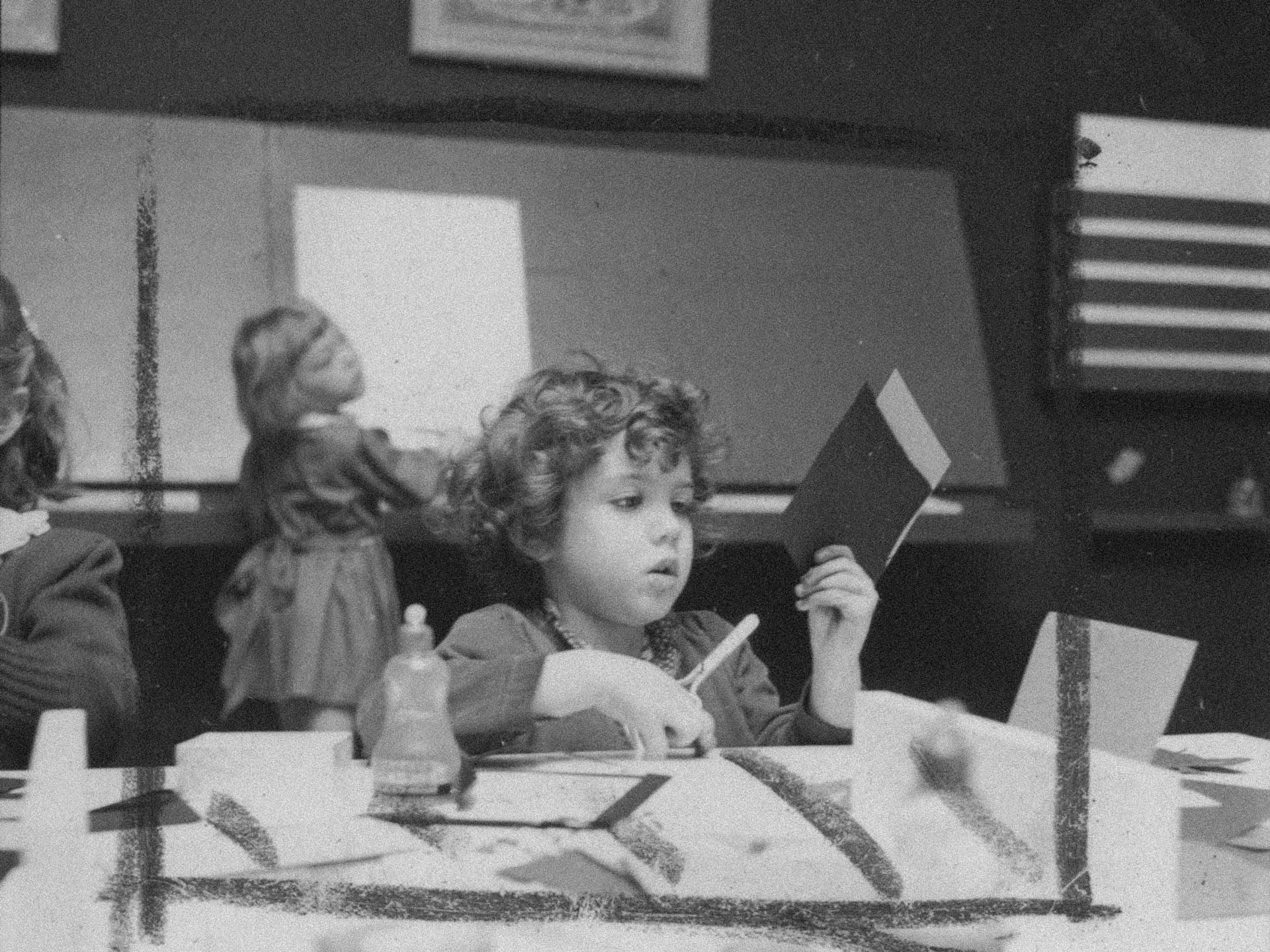

The concept of practice is an integral aspect of being human: doing something repeatedly, making errors and learning from them, operating at the edges of your ability, and, most valuable of all, the satisfaction gained from improvement.

Practice is more than just repetition of behavior—it’s a movement of energy that creates a fissure in us to reveal what’s within. More movement, more revelation. Among the many things we discover about ourselves when engaged in the practice of writing or dance or making music is how to live with meaning and intention, which is perhaps the most important discovery of all.

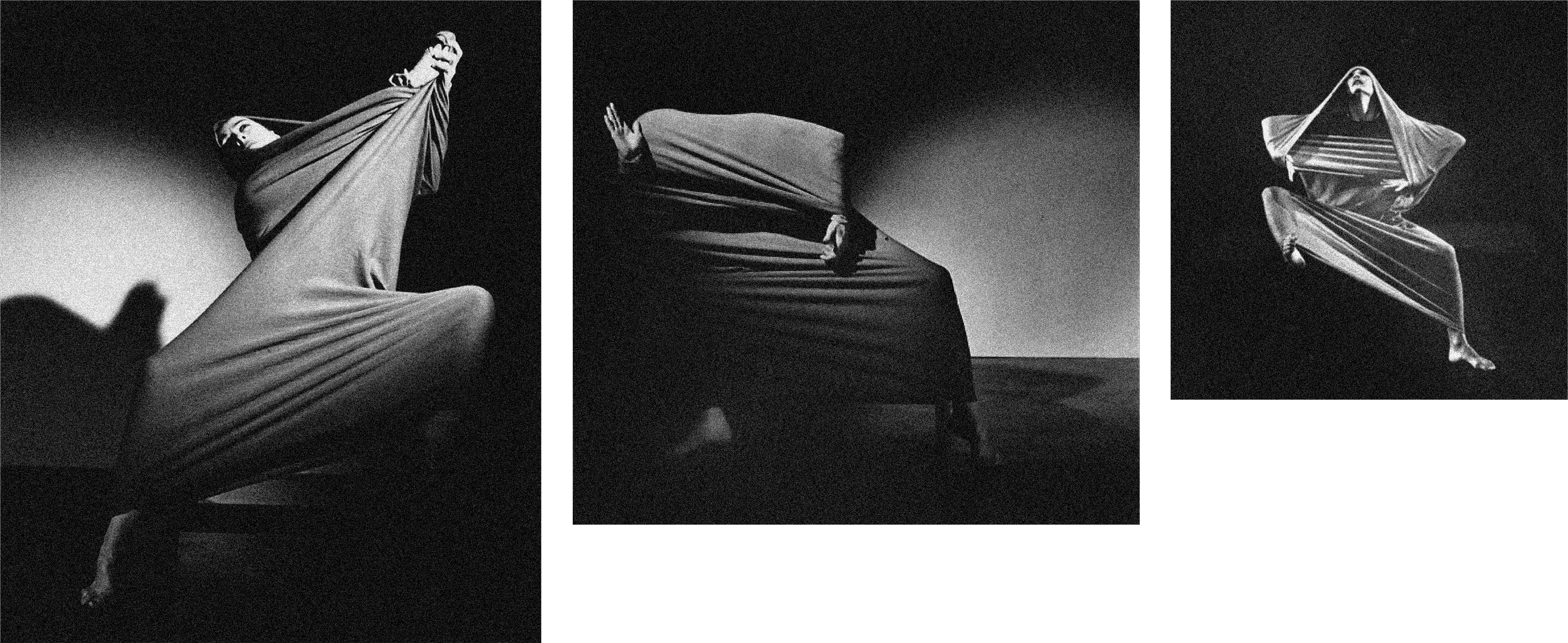

Legendary choreographer and dancer Martha Graham masterfully expresses this in her essay in This I Believe: The Personal Philosophies of Remarkable Men and Women:

“Whether it means to learn to dance by practicing dancing or to learn to live by practicing living, the principles are the same. In each it is the performance of a dedicated precise set of acts, physical or intellectual, from which comes shape of achievement, a sense of one’s being, a satisfaction of spirit. . . . Practice means to perform, over and over again in the face of all obstacles, some act of vision, of faith, of desire. Practice is a means of inviting the perfection desired.”

The last thought—“inviting the perfection desired”—is earned wisdom. How many bruised toes and turned ankles did Martha Graham have to experience to arrive at this understanding of her art?

She tells us: “Dancing appears glamorous, easy, delightful. But the path to the paradise of that achievement is not easier than any other. There is fatigue so great that the body cries, even in its sleep. There are times of complete frustration; there are daily small deaths.”

Despite daily deaths, she loved her craft. She wrapped up her wounds, stretched, and kept going. She knew that daily deaths were part of the practice.

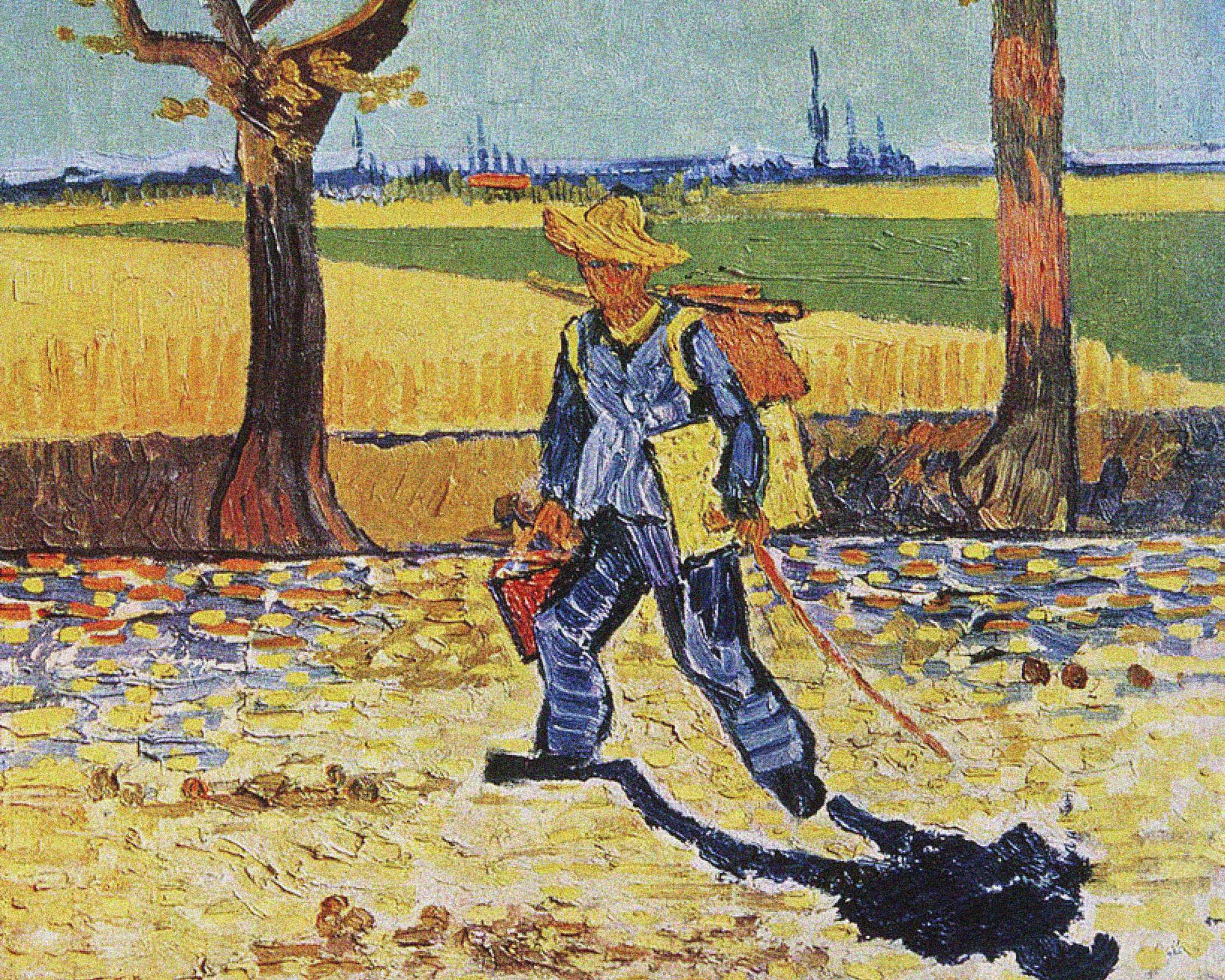

Go to any art museum, and you’ll notice students sitting in front of a master’s painting. Look over their shoulder and you’ll see them sketching and observing for hours. They’re practicing.

The student that builds the habit in learning from the masters will inevitably, over time, find her voice, her subject, her technique. She is practicing the skill of learning how to see. She is practicing the subtle, yet vital, habit of showing up—even if (and especially when) she doesn’t want to.

Every time she buys that ticket and shows up to the museum, she is “inviting the perfection desired.” That is where her Muse is.

The idea seems simple: To be a creative person, to lead a fruitful creative career, keep practicing! Keep making and putting projects out into the world. On paper, the math doesn’t get any clearer.

But when a freshly enlightened artist-to-be dares to sit at a piano or wander their neighborhood with a camera or buy a sketchbook and some micron pens, they’ve entered a new frontier. They are no longer spectators of creativity; they’re in the cockpit, feeling the g-force that a creative calling entails.

To embrace and to love that feeling is also a practice.

What gets in the way of practice?

“If I skip practice for one day, I notice. If I skip practice for two days, my wife notices. If I skip practice for three days, the world notices.” — Vladimir Horowitz

For most of my life, I believed that I didn’t have a single creative bone in my body.

Over time, I told myself a story about how writing and reading were the two pillars of becoming a writer. The same way that exercising and practicing are rudimentary to being an athlete.

If practice is vital to stretching and strengthening our creativity, then what stands in the way?

Below are some roadblocks, both real and imagined, that are helpful to be aware of as you endeavor to practice.

Resistance

Naming things gives form to the unfamiliar and gives us back power.

Everyone has the voice in their head that feeds self-sabotage, self-doubt, and self-loathing. What is that voice and why does it show it up precisely at the time when we want to launch a business, start a non-profit, or learn a new hobby?

Author Steven Pressfield gave that voice a name: Resistance. Like an invisible energy shield between your heart and a blank document, how many times have you stared at it, hoping it would write itself? Yet, a week ago, you had all the opinions and ideas in the world.

Pressfield said in his essay Resistance = Fear:

“Artists and warriors live and die by one primal emotion.

Fear.

Fear stops us from beginning our work. Or carrying it forward in the face of adversity. Or completing it when we’re so, so close.

Fear of success.

Fear of failure.

Fear of exposure.”

Practice is challenging precisely because it elicits blood, and resistance, due to fear, is like a shark that can smell it from 1,000 miles away.

Perfectionism

Nothing else has claimed more of the creative potential of millions of well-meaning people than perfectionism. We strive for perfection because we think it is a shield to keep us safe—safe from criticism, from trolls, and from being seen as a fraud.

Bullshit.

Anne Lamott says in Bird by Bird, her book about writing (and about life):

“Perfectionism is the voice of the oppressor, the enemy of the people. It will keep you cramped and insane your whole life, and it is the main obstacle between you and a shitty first draft.

[…]

“Perfectionism is a mean, frozen form of idealism, while messes are the artist’s true friend. What people somehow (inadvertently, I’m sure) forgot to mention when we were children was that we need to make messes in order to find out who we are and why we are here — and, by extension, what we’re supposed to be writing.”

If you’ve ever wanted to create but you can’t stand the thought of the “mess” you might make before reaching your end goal, or you can’t fathom writing a shitty first draft (and second draft, and third draft), then perfectionism got one on you.

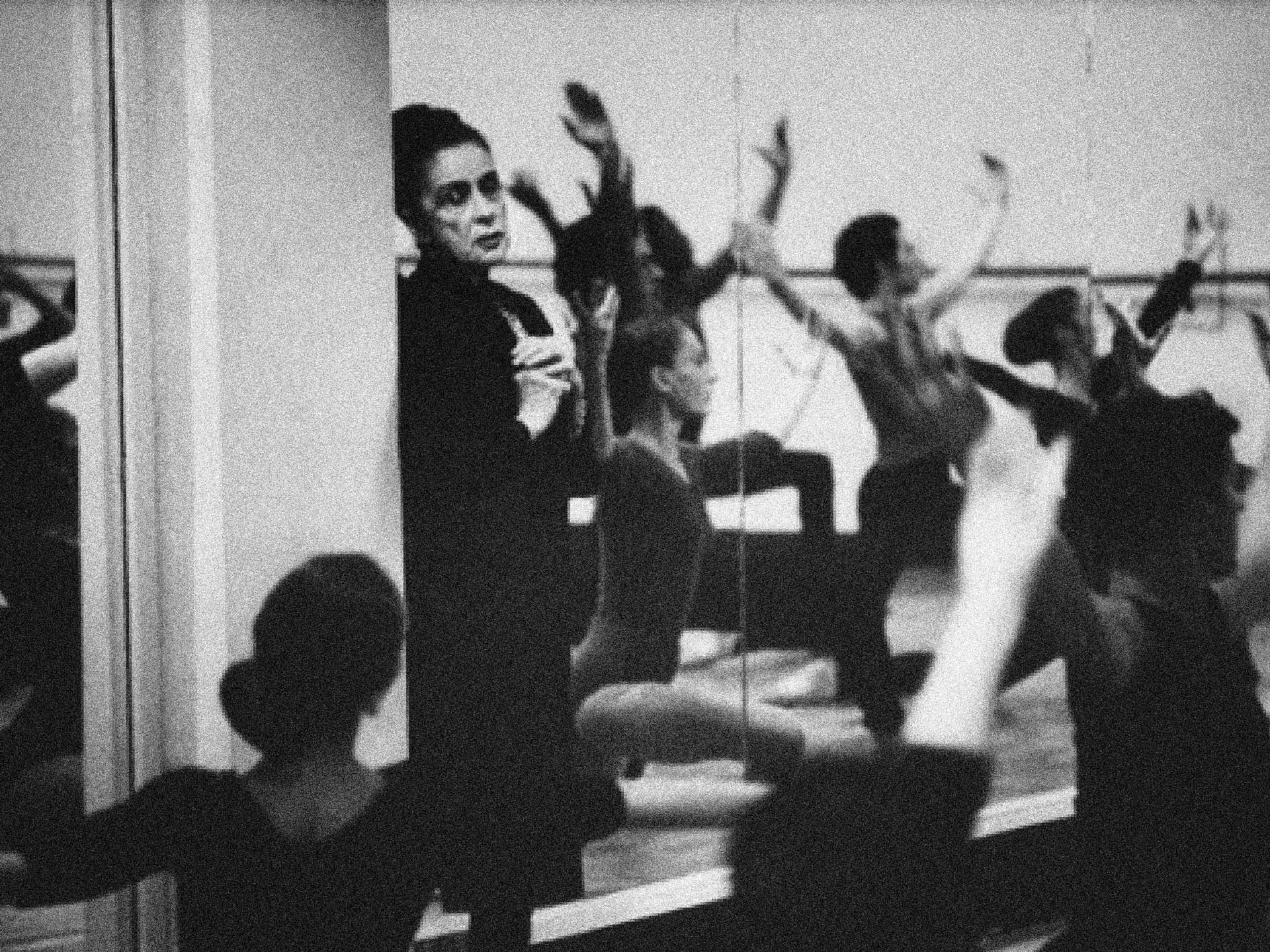

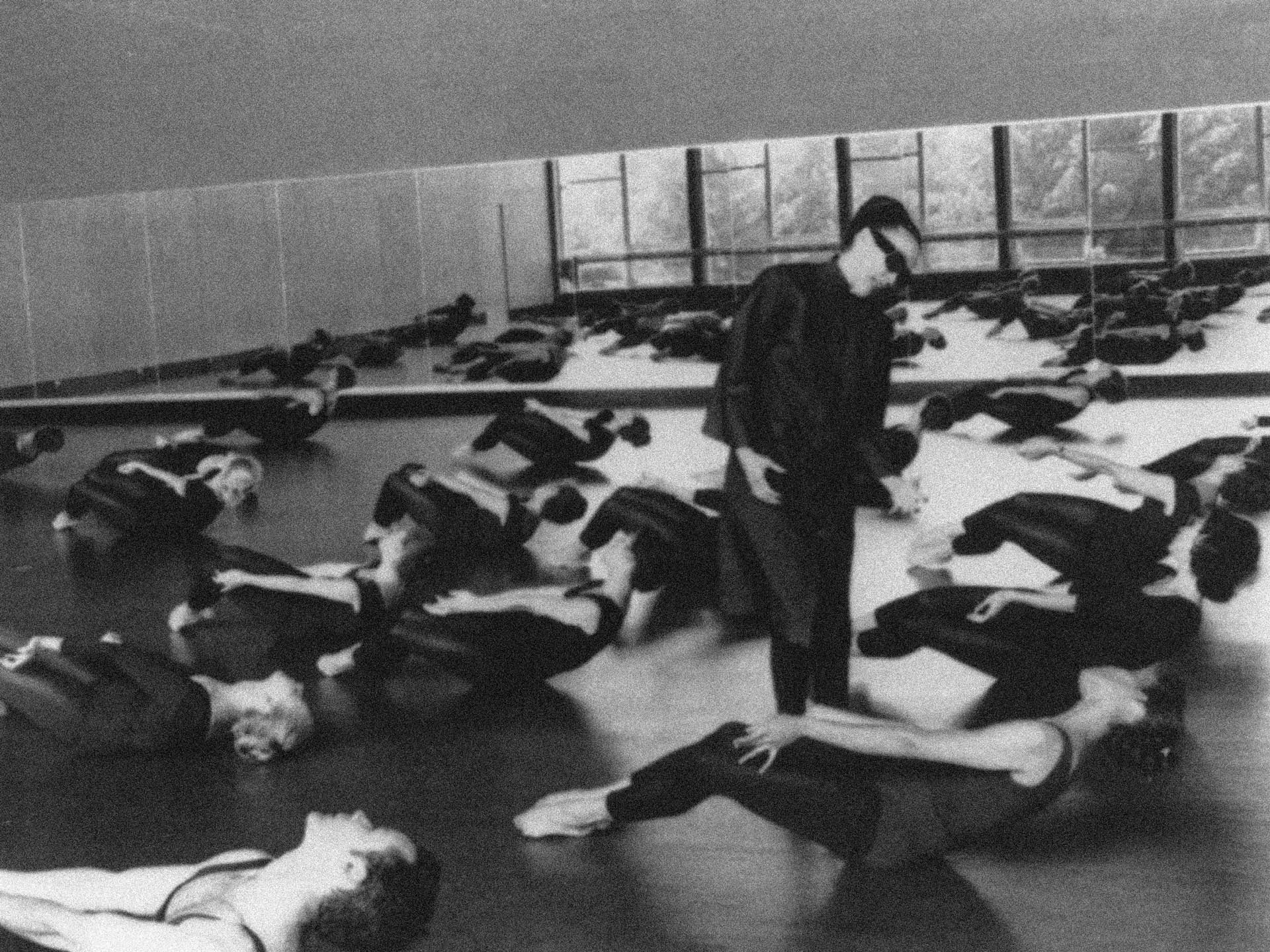

Lack of a ritual

Every creative person who is still in the game, even after both success and failure, has a ritual. They earned their achievements because they never gave up practicing and “ritualizing” their creativity. Rather than relying on sheer willpower to commit to a daily practice, they leveraged something far more powerful: ritual. A habit.

My favorite example of the importance of rituals comes from the choreographer Twyla Tharp, recorded in Mason Currey’s book Daily Rituals:

“I begin each day of my life with a ritual: I wake up at 5:30 a.m., put on workout clothes, my leg warmers, my sweatshirt, and my hat. I walk outside my Manhattan home, hail a taxi, and tell the driver to take me to the Pumping Iron gym at 91st Street and First Avenue, where I work out for two hours. The ritual is not the stretching and weight training I put my body through each morning at the gym; the ritual is the cab. The moment I tell the driver where to go I have completed the ritual.”

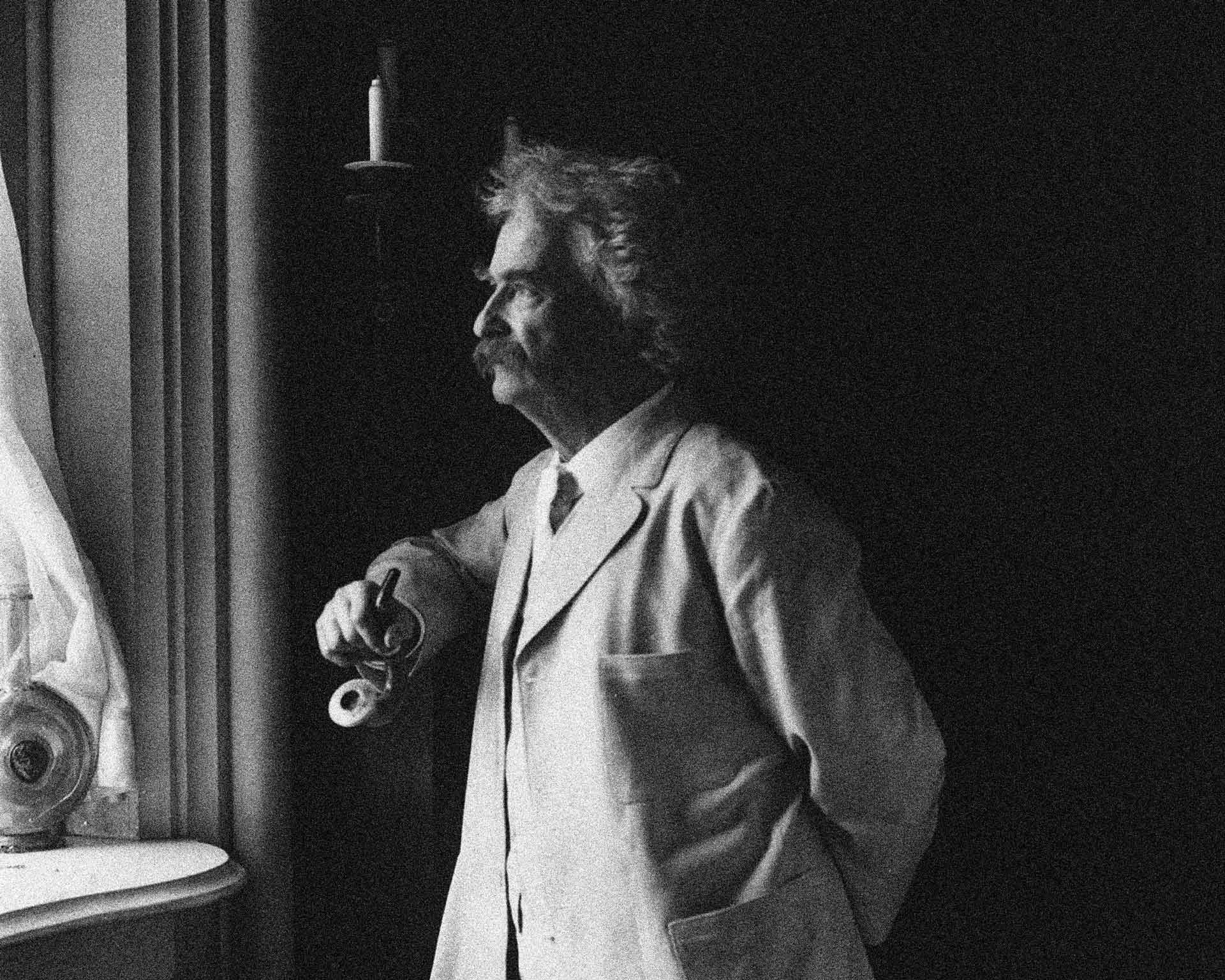

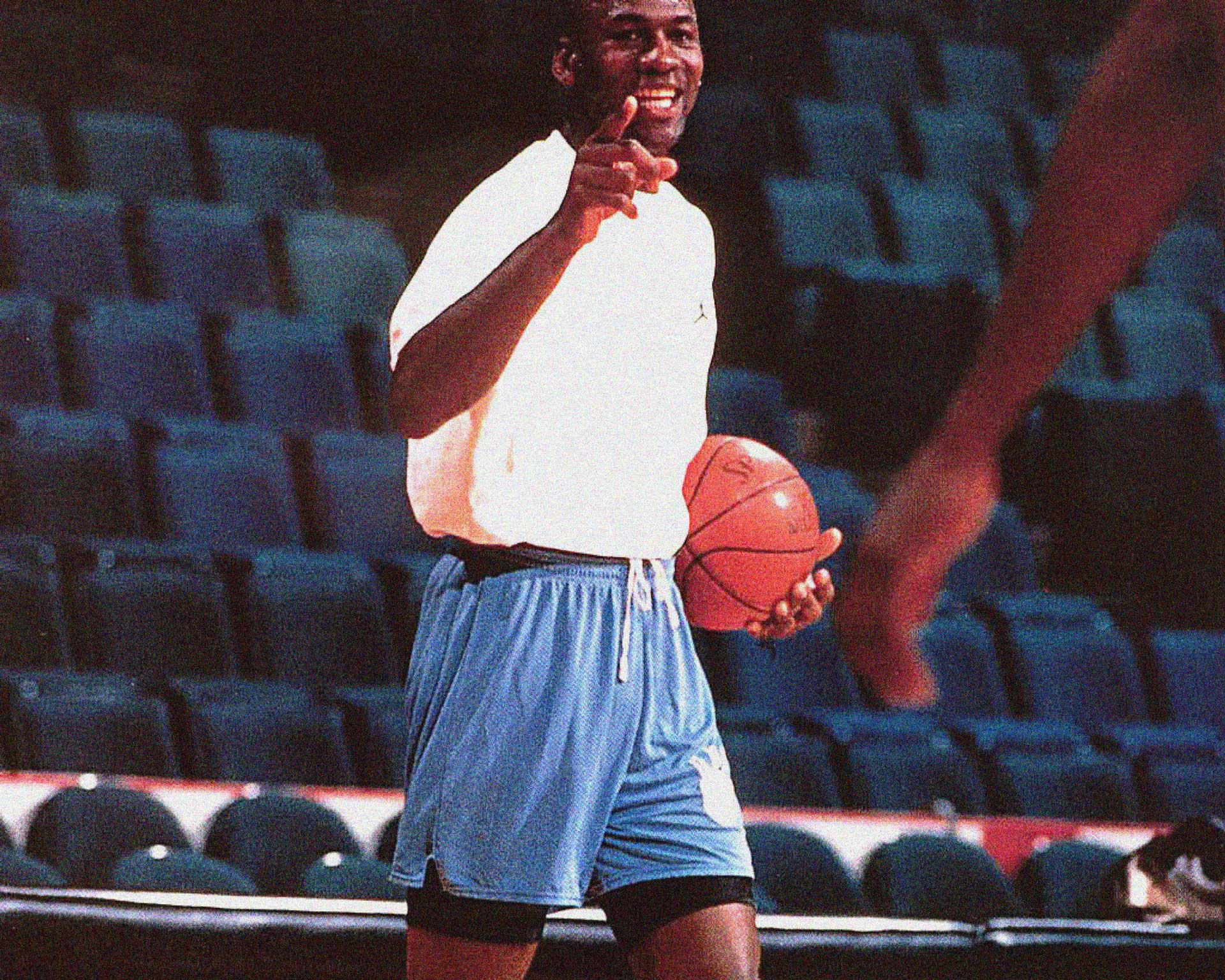

Artists and athletes share the same principle of creating rituals: Mark Twain wrote standing up, facing a bookshelf, with his typewriter on top. Matisse worked from nine to noon and then had lunch; he knew he had three hours to produce his best work before his afternoon nap. Isabel Allende started all of her books on January 18th. Michael Jordan wore his college basketball shorts under his game shorts.

These are all examples of professional habits that combat the resistance and get your mind and body into a rhythm that is conducive for creativity.

Me? If I don’t write from the hours of 8 a.m. to 1 p.m., it isn’t happening. I’ve got four, maybe five, hours at best to crank out a shitty first draft. It took me five years to figure this out and another five to own it.

And you can’t watch me work; you have to leave the room.

Love compels us

Lastly, I want to talk about love.

This thing you do every day, no matter how annoying or painful or stressful it might be. Why do you do it?

The passing of basketball star Kobe Bryant was heartbreaking, to say the least. I grew up whispering “Kobe” whenever I shot anything into a bucket. When you heard his name, you thought about his performance on the court. And if you grew up playing sports like me, you immediately thought of how hard he worked at perfecting the game he loved. He embodied what relentless practice can do to one’s craft, and in turn, one’s legacy.

I look at all creative labor in the same way. Many of us heard from an early age that practice makes perfect. What they didn’t tell us is that the bar for perfection inches further and further away from us the more we keep practicing—that’s the point.

It makes life meaningful. And it’s a behavior that consistently opens you up to new insights about who you are and why you’re here.

That makes practice worth every hour, every bit of pain, and all of the joy that it may bring.

Paul Jun is the Editorial Director of COLLINS.

Artwork by Zuzanna Rogatty, COLLINS.