C onstraints can sound negative. On the other side of that same coin is an advantage. Learning to flip constraints to your benefit is a skill, one that compounds creativity, not constrain it.

Can language be a shared constraint that boosts creativity?

This thought made me question the word “community.” In recent years, the title Community Builder has popped up everywhere from early start-ups to established brands. Companies are wondering how they can gather their raving fans or product evangelists to make people feel like they belong to something.

So, I reached out to my friends who have been at the forefront of this practice. People & Company is made up of three wonderful humans: Bailey Richardson, Kevin Huynh, and Kai Elmer Sotto. Their philosophy is that you build a community with people, not for them.

They remove the ambiguity around community building. Organizations like Nike, Substack, and Porsche trust them to take an intentional, iterative approach to connecting the people that use their products. Their methodology is based on hundreds of interviews, trainings, and collaborations plus, their own hands-on experience building communities on a global scale.

Kevin represented his team in this interview, and we dig deep into how developing language around community building helped them become better coaches for their clients, why it’s not about giving advice but about asking better questions, and other bits of wisdom on what community really means to them, how it can add value to a brand, and why the distinction between online and in-person communities is unhelpful.

Take us to the beginning. How and why did People & Company start?

We signed our first project before we had a bank account open. We had a client who really trusted us, and they needed help investing in building a community with the best people on their platform. What were we going to do about it?

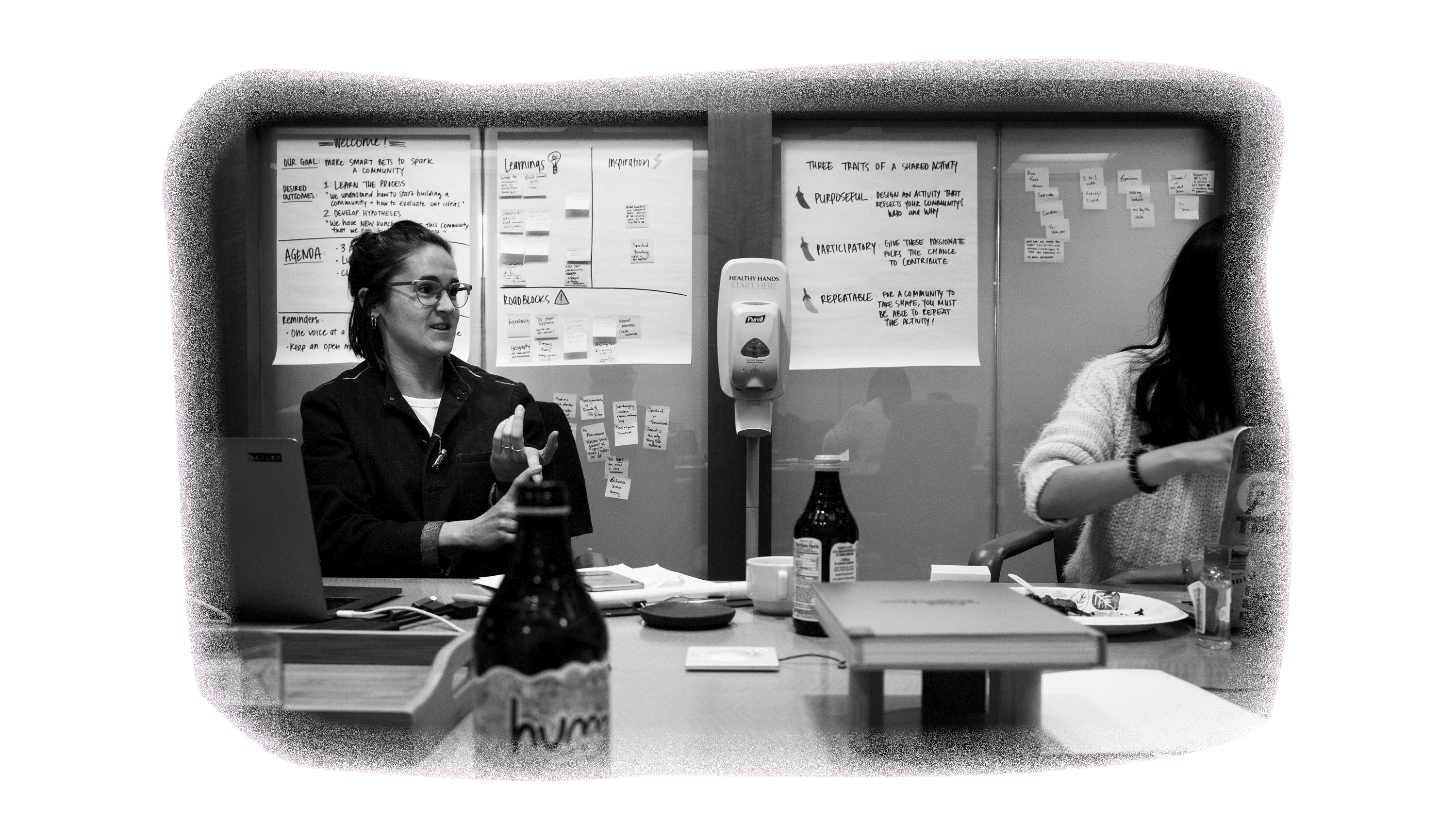

Our first challenge was to communicate how to build a community if we were going to go in and work with clients to build one. Plain and simple. I remember us mapping this out across multiple sheets of paper: What do you feel is most important to start with? What comes next? What is something that is so important later on?

When we decided to embark on writing a book, we paired that process with stories that best communicated and brought these steps to life. If a community is like a fire, how do you spark the flame? How do you stoke the fire? How do you pass the torch in the community?

One of the things I did not expect was that the act of writing this book and bringing it together would enable us to do even better work. We started this company trying to build communities for clients. Now, I think this language enables us to build it with clients. We can really jam with another group of people on how to build a community because we can land these concepts in firm language and a clear step-by-step process.

Any personal revelations that you learned along the way?

I started at People & Company from a place of I believe I have best practices to share. I believe I have advice to give.

What I’ve realized over time is that our clients know their people better than I do. If you’re trying to build a community of photographers, you understand photographers much better than I do. If you run an underwear company and have super fans of your underwear company, you understand your super fans of your underwear company way better than I do. Hurley understands their surfers more than I do.

Best practices and advice are just a slippery slope. You’re trying to apply lessons across different people, with different contexts and different motivations.

We had to move from consultancy to coaching. We had to go from doling out advice to asking questions and bringing people through a process. Your ideas will come from your understanding, but we can provide the structure and constraints and the names for what you’ve got to figure out.

“If a community is like a fire, how do you spark the flame? How do you stoke the fire? How do you pass the torch in the community?”

How do you define a community?

True communities are simply groups of people who keep coming together over what they care about.

A community has a couple of elements:

- It’s a specific group of people. We’re not talking about a “sense” of community or community as some industry in general; we’re talking about an actual group of humans.

- People have to keep coming together and continue to participate or contribute within this. If you get 10,000 people to show up at a marketing event, that’s great and all, but that’s not a community.

- Community members are drawn together by the thing they collectively care about. That passion point is the connective tissue, and is where so much of this magic is. There are lots of different people who care about lots of different things, but there is some common sense of a purpose, passion, or pain that these folks are trying to gather around, explore, go deep, or interact on with one another.

Communities feel magical, but they don’t come together by magic.

One key stage in your methodology, and one that’s sometimes overlooked in our digital world, is the development of a “shared activity.” Can you define a “shared activity”?

Whether online or IRL, communities of all stripes form around shared activities. No matter if you’re a community that comes together to test recipes, navigate personal finances, write, or ride bikes, your members bring the community to life through this thing they do together. In other words, kindred spirits operating in silos aren’t a community (yet!).

What makes a successful shared activity is three things: it’s purposeful, it’s participatory, and it’s repeatable.

Our job is to help clients hold that standard to a high level, because if they don’t, you can’t fake the funk. If it doesn’t really speak to something that the community members need, or that is important or urgent, your community will lose interest. That doesn’t mean it has to be serious or fancy. It could be fun or it could be simple, but it really has to deliver on the promise of this group.

All of that said, there are challenges now that are coming to light more than before. We’re talking about holding colleagues accountable to be anti-racist within their organizations. It’s about providing support and aid to people who are really struggling right now. It’s about just staying healthy and happy during this time. There are real, urgent needs that are out there, and I firmly believe that communities and working with other people is one really powerful tool by which we can address those things.

If you’re willing to take the first step and you have that belief that there are some people you can bring together in order to realize a purpose, then give it a shot. The rules may have changed, the ground may have shifted, but the fact of the matter is that communities will continue to play a part in people’s lives and in helping them get where they want to go.

“Communities feel magical, but they don’t come together by magic.”

A client comes to you wanting to build a community for their organization. Where do you begin?

We believe the three most important foundational questions for any community are:

- Who are you trying to bring together?

- Why are they going to come together?

- What are they going to do together?

Let’s take a coffee brand. Are you trying to focus on the fanatical customers because they bring the most passion? Or are you thinking about a burgeoning group of customers that you want to partner with? Are you thinking about the most knowledgeable people who have insightful feedback for your product? If you don’t know Who you’re focused on with a community building investment. Organizations that jump to tactics without pausing to know who they are serving risk building a community no one actually wants or needs.

Then we help clients understand who specifically those people are, and why those people will come together. Is it emotional support? Is it inspiration or fandom? Is it something else? And what will they do together? Does this look like virtual events? Does this look like contributing to a knowledge base? Does this look like a challenge? Does this look like a small group or circle? Whatever it is, that’s kind of where we hang.

We tee up these three key questions very early on and make it clear that this is where we believe we should start. Even if they don’t work with us for whatever reason and they only have this first conversation with us, I’m happy equipping them with what I believe are the most productive questions to really focus on.

I love this. Just between the three of you and your extensive backgrounds, it seems like the team has the answers.

I disagree that we have the answers. I believe we have standards for what makes a good answer and it’s our job to hold clients to that standard.

It’s like how a college professor can’t write the essay that you can write, but they can definitely hold you to a certain standard to communicate your ideas and beliefs.

Do you ever deal with tension or conflict around the language of community? Because you’re asking questions, you’re allowing them to share their worldview and understanding, how they see it in the context of their work, and ultimately the benefit of the company.

I think if there’s any conflict, it’s actually not with us, it’s between the clients themselves. That’s a benefit that we do not explicitly sell—the fact that we are going to provide a space for a cross-functional group of team members who don’t talk enough to actually talk about these things and ask questions and hopefully resolve any internal conflict that is already present there.

If there’s any conflict, I believe the seeds of it are already sown and we provide, hopefully, a safe and productive space to have these hard conversations around priorities.

Right now, there is this line in the sand between in-person communities and online communities. Thoughts on that?

I believe it’s an unhelpful distinction. I think dividing communities as online versus offline isn’t helpful to community leaders who are actively thinking about what they’re doing, like how to make the best decisions right now to cultivate a stronger group.

Back to our definition: True communities are simply groups of people who keep coming together about what they care about.

Nowhere in that does it define this group of people as an online or offline thing. It actually comes down to the group of people. Let’s think about what’s happening with COVID right now. We do some work, for instance, with the Surfrider Foundation that has a community of ocean and coastline activists around the world, and I would say most of their shared activities take place in-person. Beach cleanups and organizing other local actions that happen in-person. And what they need to do, at least in the short-term, is shift what they do together.

What’s more helpful, instead of categorizing the community itself, is categorizing the activities as primarily online or offline. That’s what makes sense for me.

If you think about the Instant Pot community, they share their successes and failures of what they cook in their Instant Pots on social media, but they had to cook that thing in person. So where do you draw the line? Your watering hole where people share what’s happening is online, but if you’re thinking about what community members do and what really motivates them, categorizing into the online or offline realm isn’t what’s helpful.

What is helpful is to go back to those core questions: Who are we bringing together? Are they ocean activists or are they Instant Pot-heads? And more importantly, especially in this moment: Why are they coming together? What is the purpose of this group? Does that purpose still hold true today? Or does it need a bit of a remix?

People came to Surfrider to pool resources and make a collective impact — that’s what it was all about. Are they now coming back to this community for some sense of emotional support or fun in a time that’s really challenging? If we acknowledge what we want to optimize for, what we want to accomplish as a group, that can inform what we do together next. So instead of asking if it’s making a collective impact with issues that relate to protecting the oceans and beaches, we might ask “How can you do that asynchronously? How might you do that without meeting up in large groups?” If we acknowledge that some of this community’s purpose is to keep them feeling inspired and connected, then perhaps you’re going to organize activities optimized for feelings, check-ins, or just a little bit of fun and reprieve from a lot of the stresses of today.

At the end of the day, I think what’s most helpful is to root yourself in the purpose of the group. Who are you bringing together and why are they coming together? That second question is one of the things that you may not fully answer. It’s a moving target. It’s one of those things you have a hypothesis for, and you try to get a better understanding of it over time. If you at least have a hunch for it, you’re going to be better equipped to decide what to do together.

Zooming out a bit—what are your and your team’s thoughts on creativity and design as tools to build new futures?

Our whole company and our partnership is like a creative experiment. I am grateful that, I believe, we continue to exercise creativity day in and day out, year in and year out, to try to shape this organization into something we’re proud of that can better realize our mission to bridge gaps by helping get people together.

Whether that is continuing to work with clients one-on-one or to do a little bit less of the guidance and more of the inspiration around what communities can look like, what we want to highlight is that these are extraordinary communities built by ordinary people.

“At the end of the day, I think what’s most helpful is to root yourself in the purpose of the group. Who are you bringing together and why are they coming together?”

There’s a case study of Duolingo, which is an app where you can learn languages. The head of community there, Laura Nestler, was on our podcast recently. Early on, they started making these little investments around what more they could do with the people who were learning languages through their app. They realized, well, you don’t just learn a language to type it into an app. You learn a language to speak with other people. What if we worked with them to set up circles where people could practice speaking to one another?

And all of a sudden, pre-COVID, they reached around 2000 events. Every single month, 2000 language circles, physical or virtual, happening every single month and even now all virtual happening every single month.

There are plenty of ways to accomplish your goals and hit your KPIs and make money, but I believe that in building a community you have a chance to have more fun in the process and a chance of accomplishing more together with people. You also have a chance of building an organization that’s even more integrated with the people you serve, and that keeps you accountable in a certain way to really accomplishing a mission and not just making dollars.

Are there communities you are inspired by but didn’t build? Whether something you are a part of or observe from afar?

One is a fitness community called ANCKOR. About a year ago I met a guy named Brian, who had realized that fitness was an amazing way to explore some of the emotions in mental health. He questioned why nobody had really optimized to do this; people go to work out to blow off some steam or figure something out or get realigned emotionally. He was doing these small-group-circles-meets-body-weight-HIIT-workout sort of stuff in person. And then when COVID hit, he quickly started doing it online, but it wasn’t like he just tried to copy and paste. He really remade ANCKOR to fit for this period of time and it almost was more successful online. To be able to check in with other people around the world was really powerful.

I’ve been a hand raiser for this group, and I continue to work out with them and communicate with the people there and that’s been a healthy drum beat.

The other one that comes to mind is a community called Allyship & Action, started by my friends Nate Nichols and his business partner and wife, Steffi Behringer. He started an advertising agency called Palette Group where they did production for video shoots and when COVID hit, his clients just disappeared. They decided, “We’re freelancers, we’re creatives, why don’t we just organize a summit to help people figure out what the fuck we are supposed to do right now?”

They started this thing called Freelancer Cyber Summit and gathered hundreds of people over the course of the first two or three summits.

Then with the murder of George Floyd, Nate, who’s Black, said he woke up that day and he felt like it was one of the first moments that people were starting to see the weight and the trauma that he’d been carrying and all of the walls that he had to jump over just get to the position where he is, which is still just trying to figure out how to run this small business in this time.

Nate and Steffi stepped up as leaders in that moment and they announced that the next Freelancer Cyber Summit was going to be about Allyship & Action. It’s about anti-racism in the advertising industry and they spun this up within one or two weeks.

Literally two weeks later around 3000 people signed in, watching the live stream for this day of panels and talks and workshops and a Slack community to follow it. They’re asking questions around how can white agency leaders be better allies? Just really going straight to it and getting the CEOs of agencies to participate. They’ve gone on to host their second one. It kind of gets back to this point of holding those standards high. It’s not like no one wants to participate in any activities and I get that people feel Zoomed out, but the fact of the matter is if you do something that people really need or want and provide them an outlet to express or explore something that they’ve been itching to, the participation will be there.

Allyship & Action is one of those scenarios. Equipped with what we have, with the knowledge and the network we have at People & Company, we can invest in helping other leaders who know their people and know certain challenges way better than we do.

The last thing I’ll leave you with is that if there’s one life lesson from our book, it’s that you build a community with people and not for them. You invite people to that Zoom call, that small group circle to check in, and you enable them to participate. You aren’t just talking at them. You aren’t just presenting something to them. You aren’t just marketing something for them. You really do something with them.

Over time, that small act of collaboration can grow. Some people will immediately raise their hand and be like, “I want to do more.” But when you are able to build with others and spread out leadership in that sort of way, the organizations that we build and the products and services and initiatives that we put into the world come looking not as something hatched by a singular person, but really something that’s a living and breathing product made with many people. To me, that’s just the fucking best.

If we’re in this in order to make an impact, what better way to leave a lasting impact than to do something with people that can outlive you or your tenure on that project.

Thank you, People & Company, for the beautiful work you do, and thank you, Kevin, for these incredible insights.

Paul Jun is the Editorial Director of COLLINS

Kevin Hyunh is a partner at People and Co.

Artwork by Sanuk Kim, COLLINS.

Learn more about People & Company: Website / Book / Podcast / Twitter.